Sponsored Content

“We are the first generation to feel the effect of climate change and the last generation who can do something about it.” This is a quote from former US President Barack Obama.

The scientists of the World Weather Attribution have a very clear and unambiguous assessment of the events that we felt during the summer of 2021: The heat waves in the northwestern USA and western Canada and the severe flooding in Western Europe would have been “virtually impossible without human-caused climate change”. I would argue that this is what climate change feels like.

All our alarm bells should be ringing. Like former President Obama says, it is time for us to do something about it.

The good news is that we, as a #hydropower industry, have one of the tools in our hands that can make a decisive contribution to addressing climate change. It is certainly not the only tool that exists, but it is an important one.

As per the International Energy Agency (IEA) report, there will be no #NetZeroby2050 and climate pledges from governments will fall well short without a doubling of hydropower capacity by 2050. As IEA Director Fatih Birol says: “Hydropower is the forgotten giant of clean electricity, and it needs to be put squarely back on the agenda if countries are serious about meeting their net zero goals”.

Taking action now is possible; it is in our hands to move.

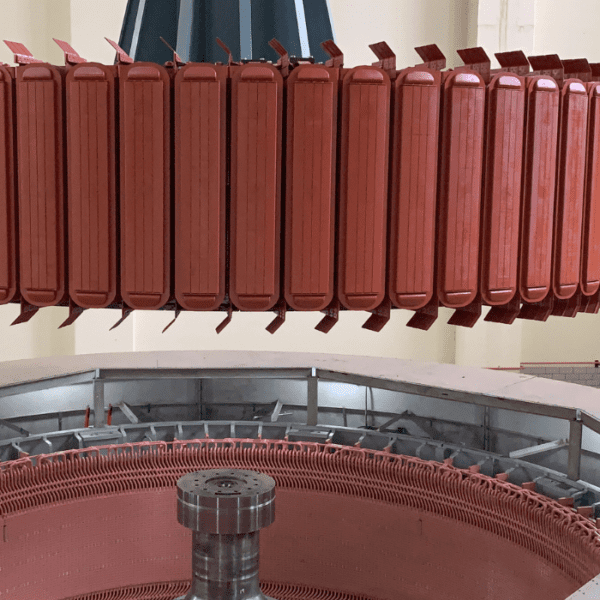

The Enabling Technology

There are several good reasons to believe in hydro storage as the technology that enables the integration of more renewable energy sources and helps ensure the path to a decarbonized energy landscape. The principle of Pumped Hydro Storage (PHS) is simple: The power of water will meet the demand when wind and solar are unavailable or absorb energy when there is a surplus — avoiding massive curtailment contributes to the overall system efficiency, ensuring that no green electron is wasted.

As the energy mix evolves, both Conventional Hydro and Pumped Hydro Storage can provide all services from reactive power support to frequency, inertia, and black-start capabilities, without CO2 emissions.

In a future grid with much less rotating mass, Hydro will become an important renewables contributor to inertial grid stability and power storage. Today, over 93% of the current storage capability in the United States comes from water storage, totaling 22.9 GW. Its storage capacity is 100 times higher than that of any available battery solution.

PHS technology is the most cost-competitive, large-scale (both in terms of energy and duration of storage), predictable, efficient, and sustainable energy storage solution. These storage facilities have a lifetime of more than 40 years for the electromechanical equipment and at least 100 years for the dam. This means that the investments we make today will be providing renewable power and grid stability services for generations to come.

This long lifetime also makes PHS the energy storage solution that offers the best performance in terms of the efficient use of resources and energy. Studies show that it will return more than 150 times the energy required for its construction across its operating lifetime, whereas other solutions do not get anywhere near this ratio.

Many PSH hydro storage projects are currently under development – about 250 GW globally – spread across several regions. Currently in the United States, there are three proposed projects with licenses from the the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), and about 70 other greenfield PHS projects in various phases of permitting and licensing, totaling about 54 GW.

Looking to the future, new hydro storage technologies will allow us to expand this potential, among other things, through the repurposing of already existing plants.

Roadblocks to be Addressed

Although everyone agrees on the need for additional capacity, what most projects have in common, is the lack of a long-term vision to address the topic of financiability. Those and other roadblocks have to be identified and addressed. There are specificities related to each country, but we can see some common trends among different markets.

Undervalued grid ancillary services – While PHS will be critical in maintaining power system stability under high levels of intermittent renewable energy, many of these services are not fully recognized nor adequately remunerated.

Lack of energy storage strategy – Most policy and market frameworks lack targets for long-duration storage, and do not adequately incentivize investment in greenfield PHS development.

Lead Time – A common barrier for PHS projects is the length of the process to build them. Hydro storage has a much longer, uncertain license timeline compared with other technologies. In some instances, it can take more than 10 years from conception to operation and obviously prevents participation in markets based on the short term. Most of the lifetime cost comes during construction, so investors need revenue certainty for the long term, which is hard to get in liberalized markets. Given those long lead times, investment decisions are needed now to ensure solutions are available ahead of market needs.

A Clear Path for Action – Now

If we look at these roadblocks, it also becomes obvious what we need to do now.

First, energy policy makers need to assess the long-duration storage and flexibility needs of their grids and integrate this in their planning processes. Providers of essential grid ancillary services should be remunerated in line with their contribution to grid stability.

Policies put in place for energy storage need to be technology-agnostic and based on fair comparison of different existing solutions.

Second, simplifying and streamlining long permitting processes should be addressed to reduce lead time while ensuring environmental impacts are properly managed. This can now be done by taking advantage of the range of internationally recognized tools for assessing the environmental and social impact of hydropower. For GE Renewable Energy Hydro Solutions, I am pleased to reiterate that we will not participate in hydropower projects which do not fully comply with the requirements set forth in the Hydropower Sustainability Standard.

Third, financing support can unlock the development of long-duration storage technology. PHS should be included in green recovery programs that put the energy transition at the core of their strategy. They should also actively participate in finance mechanisms like green bonds. The new Hydropower Climate Bonds Standard criteria clears the way for significant additional investment in sustainable hydropower.

Governments should consider recoverable grants that allow the sharing of project risks between government and developer to support private investment and development.

In designing market products, policy makers have to ensure that those products provide enough long-term revenue visibility to stimulate investment in the most efficient low carbon technologies. There are several options to do so, including ensuring appropriate contract lengths, allowing for ‘bundled’ grid services products or introducing income floor mechanisms.

Fourth, the flexibility capabilities of existing hydropower plants should be maximized through measures to incentivize their modernization. Hydropower has the potential to expand its role much further through the modernization of existing projects or electrification of existing dams. Governments should better recognize the value of dispatchable renewable energy and encourage modernization and refurbishment investments, for instance through loan guarantees or by providing long-term revenue certainty.

Fifth, and the most important action for me: Seize the momentum. Policy makers should assess the long-term storage needs of their future power systems now, so that the most efficient options, which may take longer to build, are not lost.

We – as an industry — must demonstrate what is needed so that we can ultimately bring the necessary capacities online on time to contribute to the success of the energy transition.

Let’s be clear, these pledges are not about us as an industry. Nor is it about which country or government is doing more or less. In the end, putting these pledges into immediate action is about our responsibility not only as the first generation to directly feel the consequences of climate change, but as the last generation that can do something about it.