For the rural city of King Cove, Alaska, two small hydro projects with a total installed capacity of 1.25 MW are the answer to significantly reducing longtime dependence on diesel fuel.

With the advent of the hydro projects, the city is able to reduce its consumption of diesel fuel by more than 200,000 gallons annually. When taking into consideration that King Cove, Alaska, had a yearly diesel order of 275,000 gallons, the hydro projects reduced the city’s reliance on diesel fuel by 72%, contributing to a less expensive and more sustainable environment.

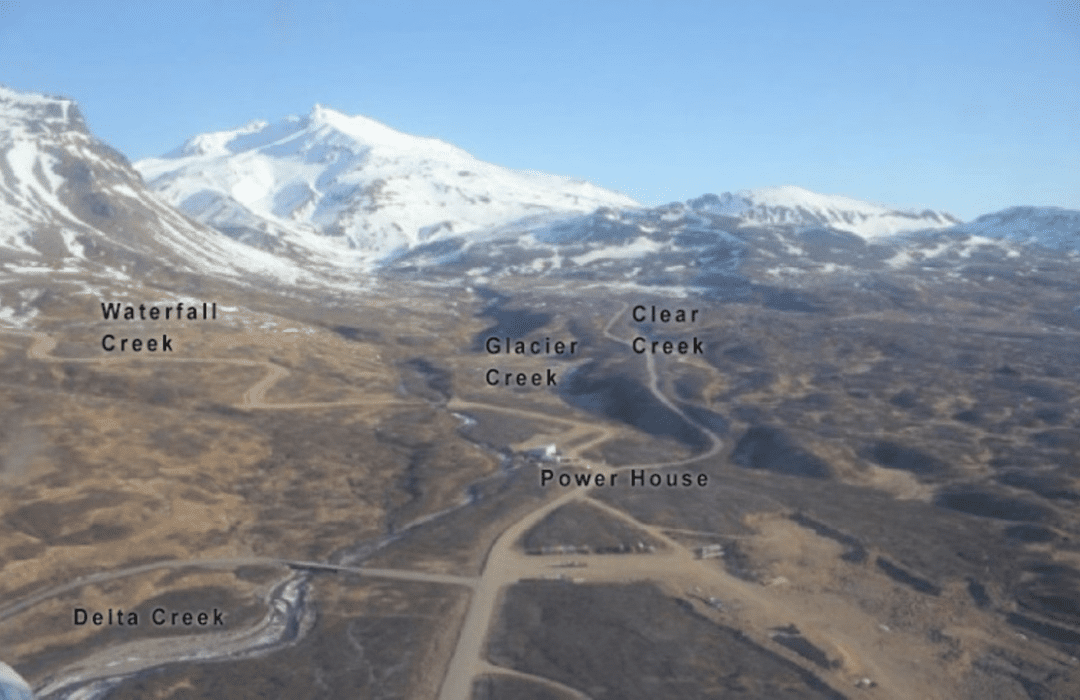

Located on the Alaskan Peninsula, the remote waterfront community’s two run-of-the-river hydro facilities produce approximately 5 megawatt-hours (MWh) of electricity annually—that’s 85% of the city’s annual demand. King Cove’s 850-kW Delta Creek Hydroelectric Project has been in operation since late 1994, and its 375-kW Waterfall Creek Hydroelectric Project was commissioned in 2017.

“One of my absolute highlights as mayor for 18 years was my hands-on involvement with our Delta Creek hydro, and more recently overseeing the construction and operation of our second hydro at Waterfall Creek,” said former King Cove Mayor Henry Mack.

Dean Gould, president, King Cove Corporation spoke about the importance of the hydropower projects: “For all King Cove Corporation shareholders, this decision was a ‘no brainer’ knowing that the incredible value of developing this hydro resource has and will continue to pay big energy dividends to our shareholders and the entire community for our generation and the many generations to follow.”

King Cove, Alaska, waterfront view.

DITCHING DIESEL DEPENDENCE

King Cove has almost 950 residents and is 625 air miles southwest of Anchorage. Founded in 1911 after Pacific American Fisheries built a salmon cannery on the shores of the Gulf of Alaska, King Cove has become one of Alaska’s largest Aleut communities, and the city has two harbors that support a year-round fisheries economy.

In the early 1990s, King Cove’s city leaders sought to extricate themselves from the financial constraints and budget uncertainty of diesel’s fluctuating cost. The year before the Delta Creek project was operational, the diesel fuel order for King Cove was 275,000 gallons, which, at the time, cost around $300,000.

With Delta Creek, diesel consumption dropped to 135,000 gallons, and with the addition of Waterfall Creek, the diesel purchase order is only about 65,000 gallons annually. While the hydro assets help the city of access sources of renewable energy, the nature of infrastructure and energy needs still necessitate the usage of some diesel fuel for electricity production.

The King Cove Corporation, which owns 90% of all the land within the city’s boundaries, includes all 100+ acres of land that supports the Delta Creek Hydro facility. King Cove Corporation was willing to enter into an initial 50-year lease for $1 to support the project.

Clear Creek impound structure.

DEEP DIVE: FUNDING CHALLENGES, PARTNERS, AND LENDERS

The encouragement for King Cove to develop Delta Creek first came from then-Alaska U.S. Senator Ted Stevens and was based on earlier reconnaissance work by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Alaska Power Association (i.e., the earlier version of today’s Alaska Energy Authority).

“Senator Stevens was on a flight with then-King Cove Mayor Harvey Mack, who hired me in November 1989 to be the city administrator and he informed me that one of my first assignments was to follow up on the Senator’s recommendation to move forward on developing Delta Creek – which I did,” said Gary Hennigh, city administrator, City of King Cove.

In 1993, then-Alaska Governor Wally Hickel jump-started funding efforts with a $250,000 match funding challenge. Funding partners included the State of Alaska, the U.S. Department of Agriculture/Rural Development, the U.S. Department of Energy/Indian Energy Program, and Aleutians East Borough.

According to Hennigh, the projects’ sizes place them outside any strict regulatory licensing authorities beyond ensuring compliance with Alaska regulations for monitoring fish permits with Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) and water rights with the Alaska Department of Natural Resources (DNR). Hennigh said that neither Delta Creek nor Waterfall Creek were subject to any Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) requirements/permits.

“Such projects in our little corner of the world that use small, run-of-river technology and with relatively few fish get to fly, rightfully so, under the FERC radar,” he said.

The Delta Creek project cost $5.7 million and was paid for through various sources. Each grant or loan required a myriad of reporting requirements, often with performance benchmarks. As the construction progressed, frequent adjustments had to be made. The construction materials list had to be accurately compiled and qualified vendors had to deliver the goods in time for each year’s relatively short construction window.

The Waterfall Creek hydro also faced construction and financing delays and challenges, including a five-month project completion delay when a new/upgraded primary transformer was needed for the powerhouse. In its early engineering phase seeking out lenders, the situation for renewable loans/grants had changed, particularly with a second installation. To make the project a reality, the city needed to step up with its own good credit. Once the construction(s) progressed so that actual costs could be compared to original estimates, frequent adjustments had to be made regularly.

It was paramount that the construction materials list was not only accurately compiled, but also that qualified vendors willing to ship to Alaska were identified who could deliver the goods and in time to take advantage of each year’s relatively short construction window. For instance, during the construction of Waterfall Creek, when it was determined that a new/upgraded primary transformer was needed for the powerhouse, waiting for the new transformer delayed project completion for five months.

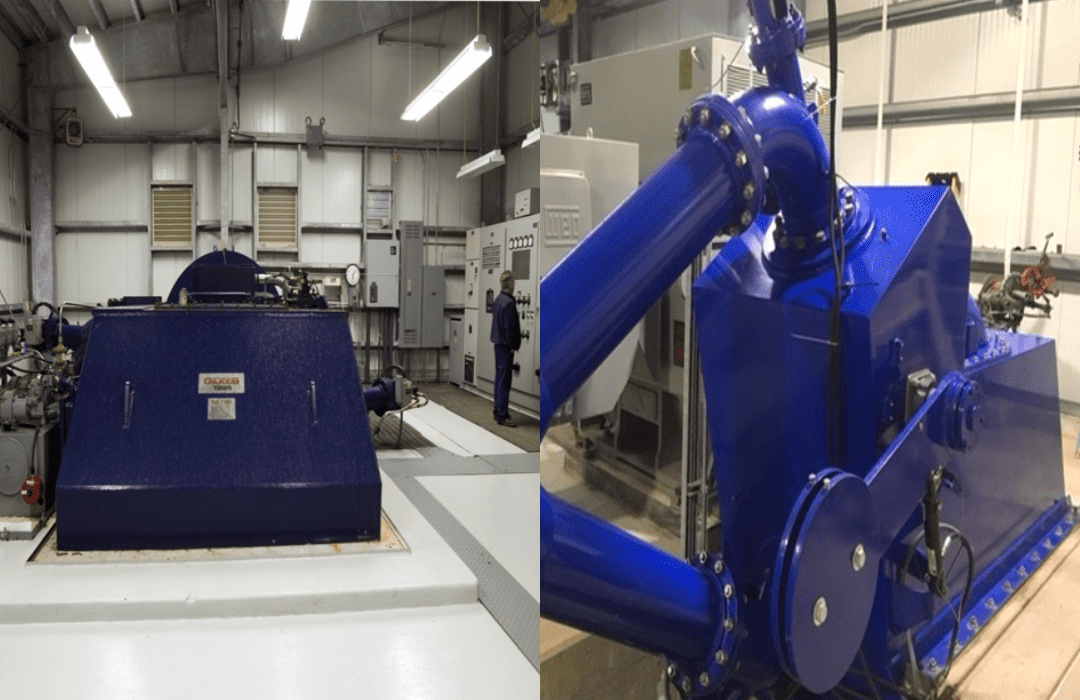

Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) controls on the left. Generators and turbines on the right.

The Waterfall Creek project, which ultimately cost $6.4 million, was financed through, and thanks to, City debt ($2.9 million), Alaska Energy Authority’s (AEA) Power Project Loan Fund ($1.4 million), and the State’s Alaska Municipal Bond Bank Authority ($1.5 million).

In taking on this considerable long-term debt, Hennigh said the community stayed “clear-eyed and focused on the even longer-term freedom it would buy from the dead-end vision of watching their diesel dollars go up in air-fouling fumes.” Hennigh said they have no regrets even as the debt service on the Waterfall Creek project costs King Cove $230,000 a year.

The permitting, final engineering, and funding for Waterfall Creek took about three times longer (years) than for Delta Creek. However, it proved worth the wait. The project has consistently outperformed initial estimates by more than 40% annual energy from 1 megawatt-hour to 1.4 megawatt-hours.

OVERCOMING EXTREME CHALLENGES

The Delta Creek and Waterfall Creek hydro projects were pursued with extreme challenges: enormous cost, a very remote area, distance complications from suppliers and contractors, the short construction season, and delays from extreme weather.

Additionally, King Cove faces wild rugged terrain, bears, active volcanoes, melting glaciers, and extreme earthquakes. Timing was crucial with ongoing delays.

The construction to garner renewable energy was tested by its remote site accessible only by air or water, extreme weather, sailing schedules for the barges to deliver the equipment and materials for the powerhouse, civil construction, and transmission lines. Construction managers were at the mercy of the fickleness of the weather and dependent upon the arrival of barges to deliver the construction materials and equipment.

Landscape overview identifying the locations of both the Delta Creek and Waterfall Creek hydropower projects.

WHY IT MATTERS

Together, both Delta Creek and Waterfall Creek now produce about 85% of King Cove’s power demand of approximately 5 megawatt-hours. Moreover, 85% of its electrical power is from a renewable source, with the least expensive, non-subsidized kilowatt-hours anywhere among rural Alaska’s 180+ utilities.

Hennigh said the city continues to subsidize the electricity for all elders (65 and older). This is now done on a sliding scale and any senior resident head-of household over 75 receives a 100% subsidy, between 70 and 74 receives 80% subsidy, and between 65-69 receive a 70% subsidy. This has been a long-standing city council recognition of the community’s elders and has been in place for the past 25 years.

“To the best of my knowledge, King Cove may be the only utility anywhere in Alaska providing this ‘gift’ for its seniors,” said Hennigh.

The year 2020 marked 25 years of hydroelectric power for King Cove and Delta Creek’s construction debt paid in full. With that accomplishment, the city celebrated relief from $150,000 in annual debt service.

Learning from both these projects has taught the city administration that the financial operating scenarios will only get better over time. Once the debt from Waterfall Creek is satisfied, these investments will easily provide another 25 years of debt-free electrical power and peace of mind, says Hennigh.