On Thursday, August 5, the California Department of Water Resources took its 750-MW Hyatt Powerplant at Lake Oroville offline. The department says this is the first time ever the plant, which began operation in 1967, has gone offline as a result of low lake levels.

“This is just one of many unprecedented impacts we are experiencing in California as a result of our climate-induced drought,” said department director Karla Nemeth. “California and much of the western part of the United States are experiencing the impacts of accelerated climate change including record-low reservoir levels due to dramatically reduced runoff this spring.”

The fact that, despite this current drought of historic proportions, hundreds of hydro plants throughout the West have continued to generate is a testament to the efforts of the owners and managers of reservoirs and generating facilities. They have managed to continue to generate electricity, offer critical flexibility for grid operators, and meet water allocation requirements in the driest conditions in a century.

“It is critical to recognize that our large reservoirs in California make periods of drought less impactful on water supply and water delivery,” says Michael Manwaring, P.G., water resources director and executive vice president for McMillen Jacobs Associates, headquartered in Seattle. “We should be grateful for having these resources available to mitigate the impacts of drought cycles, and large reservoir hydropower projects should be valued as a key renewable energy resource.”

As one asset owner and member organization of the National Hydropower Association observed, the real headline ought to be that hydro, as a whole, is continuing to generate electricity and deliver water, despite extreme drought conditions that have persisted for multiple years. That accomplishment takes continual planning, coordination, management, and an ongoing commitment to the improvement of tools to measure water flows and forecast conditions.

When the industry gathers for the Clean Currents conference and tradeshow in October in Atlanta, one of the focuses will be to share the latest tools and technologies being applied, or being developed, to more accurately predict weather patterns and future water availability.

The Deep Dive

These low reservoir levels in California didn’t “just happen.” A series of below-normal precipitation seasons have led to low water levels, not only at Lake Oroville, but throughout California.

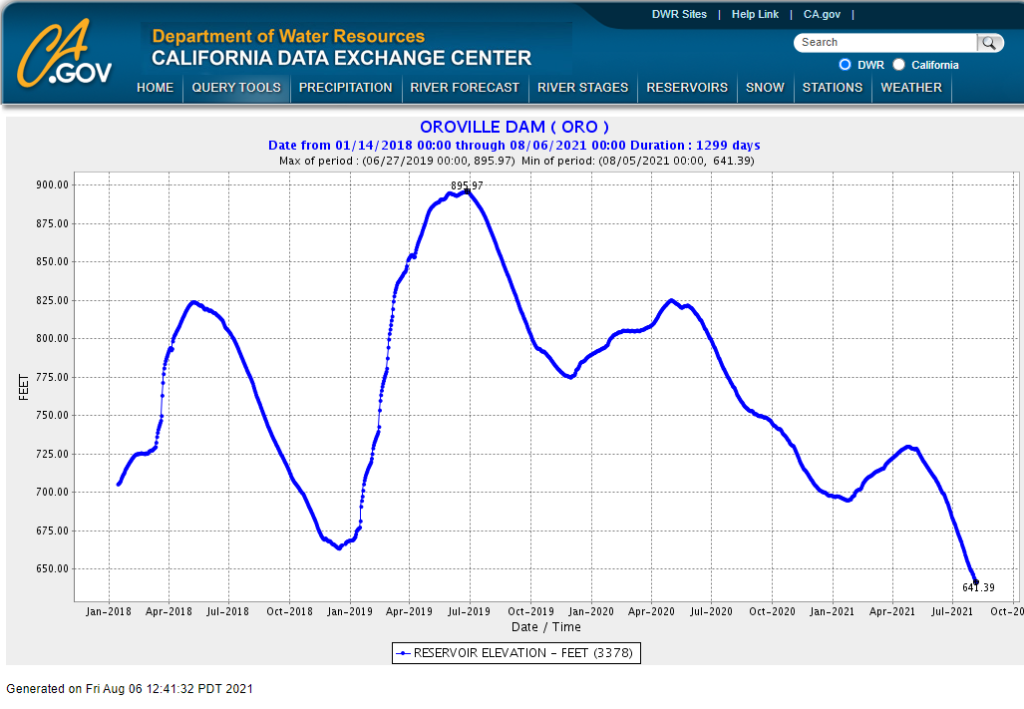

As shown in the graph below, from the California Data Exchange, Lake Oroville was essentially full (full lake level is 900 feet) in July of 2019. However, the lack of rainfall over the past two years has taken a toll on lake levels. Over the past two years, the California Department of Water Resources has worked to continue to deliver required water allocations for a variety of purposes, including domestic water supply and fish, while at the same time, to continue to generate clean, renewable electric power.

“There comes a point when it is inevitable the units will have to be shut down,” says Kevin Ballard, senior hydro specialist with Syblon Reid, a general engineering contractor based in Folsom, California.

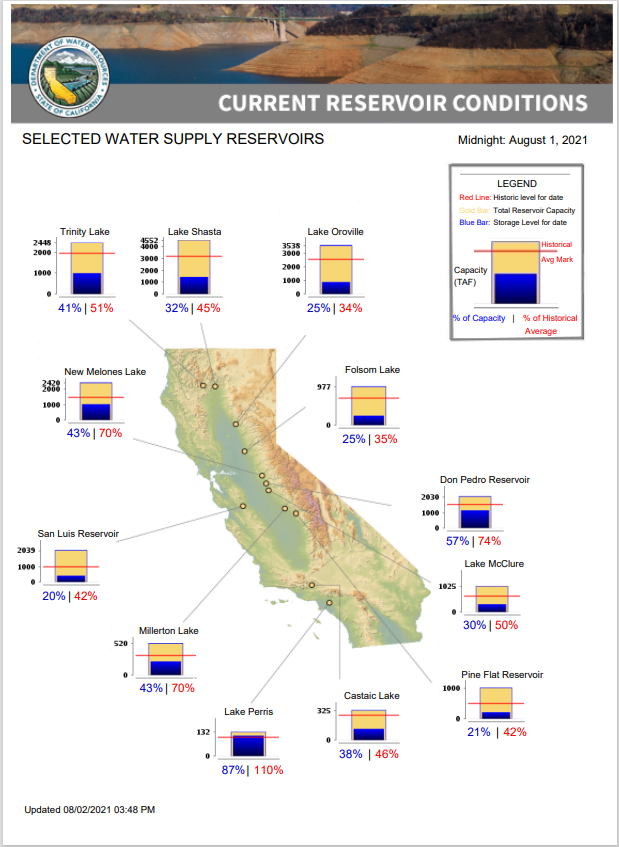

A look at current conditions at reservoirs throughout California tell a similar story to the Oroville one. The California Department of Water Resources collects and shares hydrological data to support real-time flood management and water supply needs in California. The data below collected on August 2, 2021, reflects the current storage situation of larger reservoirs in California. As Ballard points out, each watershed and each reservoir is unique and are all impacted at different elevations.

Anticipating the Inevitable

According to Department of Water Resources Director Nemeth, the department anticipated this situation at Lake Oroville, and the state has planned for its loss in both water and grid management. “We have been in regular communication about the status of Hyatt Powerplant with CAISO and the California Energy Commission,” Nemeth says.

As a result of the drought conditions causing record-setting low levels and the loss of an anticipated 1,000 MW of hydroelectric capacity, the California Public Utilities Commission, the California Energy Commission, and the California Independent System Operator (CAISO) are taking steps to ensure a balance of demand and supply on California’s electric grid. These actions include procuring additional generating capacity.

Like DWR, other owners of reservoirs and hydro projects in the West say they anticipated the effects of the drought and have been working for months to mitigate the situation. Pacific Gas and Electric Company, for example, planned ahead to stockpile available water in its reservoirs and was purposely conservative in how much water it released for hydro generation in the spring of 2021.

Project owners we talked to say managing for the drought involves plenty of coordination and communication with downstream consumptive water users as well as with resource agencies and regulators.

The same can be said for managing in times of extreme temperatures, such as the “heat dome” that occurred in June 2021 in the Pacific Northwest. Even though the demand on electric power systems during these days of 115-degree Fahrenheit temperatures was intense, the hydro project owners were able to meet electric load requirements while, at the same time, meet flow obligations for fish, recreation, and transportation.

Ultimately, these owners are working to manage the water to meet multiple demands … and doing that no matter what a changing climate throws at them. All across the West, managers of reservoirs and hydro plants are working tirelessly to do what they do, and do it well, under tremendously challenging, if not unprecedented, situations.

Despite all of this, the value hydro provides in terms of operational flexibility is still as critical as ever. As one owner we interviewed said: “To folks managing the grid, reliability of hydro isn’t any different in times of drought.”