The temperature of the Columbia and Snake Rivers increased 1.5 degrees Celsius since 1960, a trend that threatens the health of the region’s salmon and the prosperity of the people and wildlife who rely on them.

Potential causes? Climate change and dams.

The challenge? To combat the first requires the second.

The hydroelectricity produced by dams along the Columbia and Snake Rivers is the region’s #1 source of renewable energy. The dams also provide water storage for year-round irrigation and elevate water levels to transport crops by barge, a less carbon intensive method than truck or rail.

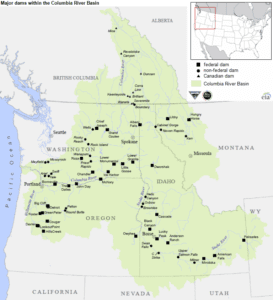

Columbia River Basin (Image: EIA)

How to thread the needle on preserving salmon habitat will depend largely on the actions of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and its new leadership. Though the new leader of EPA is from North Carolina, residents of the Pacific Northwest should feel confident in his ability to lead on this issue.

What Just Happened?

On February 9, 2021, President Biden’s nominee for Secretary of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Michael Regan, won the approval of the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee with a bipartisan vote of 14-6. In his confirmation hearing, soon-to-be Secretary Regan repeatedly emphasized his experience and success in managing complex issues in North Carolina by convening a broad array of stakeholders and sticking to the best available science. When asked of his approach to mitigation of a variety of climate change-related issues, Regan made clear his commitment to President Biden’s “whole of government” approach to the climate crises.

These skills will be useful as Regan takes over an agency tasked with an instrumental role in addressing the temperature of the Columbia and Snake Rivers.

Why Does it Matter?

In the summer of 2020, EPA released a long-awaited Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) for temperature in the Columbia and Snake Rivers. The TMDL identifies sources of heat and assigns specific reduction targets for each source. While this report is a milestone, it is far from the final step for the EPA, something stakeholders on all sides of the issue made abundantly clear in their public comments.

For starters, EPA’s engagement on this issue is necessary because the rivers span multiple states and two countries. If left to their own devices, individual states can only affect change within their borders, rather than the watershed as a whole – an inefficient process that makes it more challenging to identify the best solutions.

Second, the model used by EPA to determine the sources and allocations of increased temperature is not without fair criticism. Its scope does not cover the whole watershed, thereby potentially over or under allocating responsibility to different sources of heat. It also conflicts with the findings of other models developed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Third, EPA is an agency with expertise in both emissions and water quality. Other agencies have greater expertise in dams, irrigation, and transportation. EPA leadership and leverage of the other federal agencies can likely lead to more practical, effective, and long-lasting solutions.

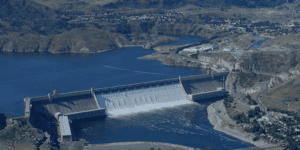

Grand Coulee Dam (Image: USBR)

What Can Nominee Regan Do About It?

Soon-to-be Secretary Regan can leverage the three things he continually emphasized in his confirmation hearing: convening stakeholders, relying on best available science, and utilizing a whole of government approach.

Step 1: Convene stakeholders

The Columbia and Snake Rivers are the lifeblood of the region’s economy, providing water and power for millions of residents. The diversity of interests and viewpoints is broad, ranging from tribes, farmers, commercial fishermen, climate activists, conservationists, elected officials, and Canadians, to name a few. As Secretary of the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality, Regan traveled to 90 of the state’s 100 counties (would’ve been 100 if not for COVID) to hear from stakeholders on a variety of complex issues. Using the same approach in the Pacific Northwest will help ensure that everyone’s voice is heard.

Step 2: Rely on the best available science

The EPA has a wealth of staff expertise and resources at the Secretary’s fingertips. The same is true for NOAA, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), and the Corps of Engineers, who have all created similar models to the one used by EPA. Given the discrepancy in the EPA’s model compared to others and the identified shortcomings, a continued emphasis on model development, refinement, and comparison will help ensure stakeholders are discussing the same set of accurate facts in the years to come.

Step 3: Utilize a ‘whole of government’ approach

The sources of heat identified by the EPA – climate change and dams – are only partially within the EPA’s jurisdiction. By leveraging the full resources of the federal government, the EPA can expand the tools in its toolkit to address this issue. Regan made it clear that EPA alone cannot regulate the nation and world out of the climate crisis – the issues are too broad and complex.

The same is true when it comes to the nation’s dams: there are 90,000 dams in the United States, only 2,400 feature a power-generation component, and each dam has its own set of uniquely complicated issues. Environmental improvements can help preserve the essential clean electricity generated with the water impounded by these dams. There are reservoir management techniques and technologies to address water temperature, but expertise on those subjects lies within the U.S. Department of Energy, its national laboratories, and other federal and state agencies.

The Salmonids are the icon of the Pacific Northwest (even though they lost to a squid in the latest bid to represent a Seattle sports team). Their annual migrations to and from the headwaters of the Columbia and Snake Rivers define way of life in the region even more so than Stumptown coffee or Beecher’s cheese. The question is not whether to preserve their habitat, but how. Soon-to-be Secretary Regan can contribute to this effort by relying on these three familiar steps.